Exhibit Trends

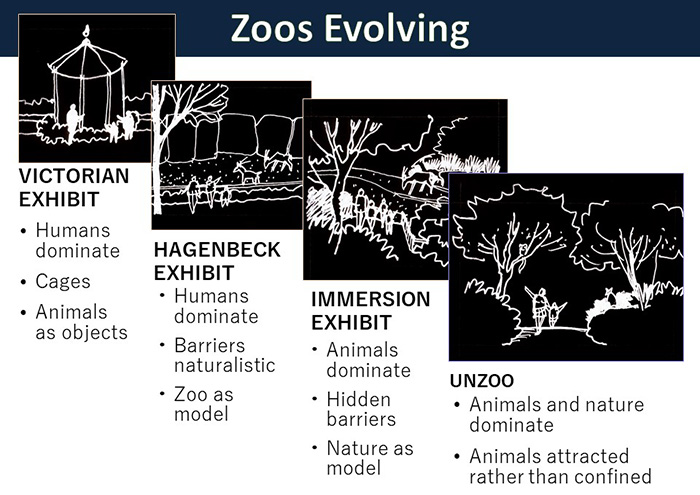

Exhibit Evolution

Like all forms of evolution, existing zoo forms don’t necessarily disappear as new forms appear. Zoo evolution is branching, not linear. Royal animal collections and popular animal-based entertainment existed in the ancient past, exist today, and will exist in the future. Excellence in many fields occurs in elite zoos but is sadly lacking in most zoos and sanctuaries when considered globally. Even the best zoos have better and worse facilities and programs. Zoo evolution occurs in multiple areas, such visitor experience, theme, and education, animal management, welfare, breeding and conservation, caregiver and other staff training, productivity, safety and gender equity, and business style. While these subjects tend to be considered separately, they evolve in sometimes discordant concert. Advanced animal welfare is not possible without sustainable financial support.

Taxonomic

The earliest zoos and menageries were organized, if at all, as collections of curiosities or displays of royal and imperial power. The first scientific collections in major European capitals were often organized into scientific taxonomic groups such as birds, reptiles, carnivorous mammals, and such by learned men for learned men.

Zoo Geographic

Carl Hagenbeck broke with tradition, organizing his Tierpark Hagenbeck in Hamburg Germany into geographic zones such as Africa, South America, and such (now called zoo-geographic display organization) in 1907. Exhibits emphasized romantic landscapes of mountains and plains and were the first true theme park. The Hagenbeck model was widely copied, abstracted, and modernized. Many of his inventions such as artificial geologic features, hidden moat barriers and overlapping vistas are important features of modern zoo exhibit designs.

Naturalistic Habitat

Many zoos seek to represent displayed animals in simulations of their natural habitat, sometimes with considerable detail. But typically, visitors stay outside in a generalized park landscape looking into the naturalistic animal enclosure.

Landscape (natural habitat) Immersion

The goal of immersion design is to immerse animals and guests inside the same re-created theme area, habitat, or landscape. Animals and visitors are separated by hidden barriers but share the same landscapes. Barriers, buildings and other “unnatural features” are hidden. In its purest sense, landscape immersion design takes the position “nature is the best model“. This concept has gradually gained world-wide acceptance and is often considered “best practice”. Good examples include most animal displays at Woodland Park Zoo in Seattle, many displays at the Bronx Zoo, especially the Congo Forest, Jungle World, Madagascar, and Tiger Mountain. Other examples include the Masoala Madagascar Rainforest at Zoo Zurich, Ford African Rainforest and African Plains at Zoo Atlanta, the Arizona Sonora Desert Museum and the Singapore Zoo and Singapore Night Safari.

The landscape immersion approach arose from the naturalistic exhibit traditions of Hagenbeck and Akeley. It is responsive to our increased concern to protect wild animals and wild places by educating and involving urban populations. This approach benefited mutually from parallel development in exhibit materials technology and craft and the introduction of contextual exhibits in museums. Use of immersion exhibits seems to give great scope to affective learning and based on its present popularity, adds important recreational dimensions as well.

Quoted from “Landscape Immersion —- Origins and Concepts ” by Jon Coe 1994 AZA Annual Conference Proceedings.

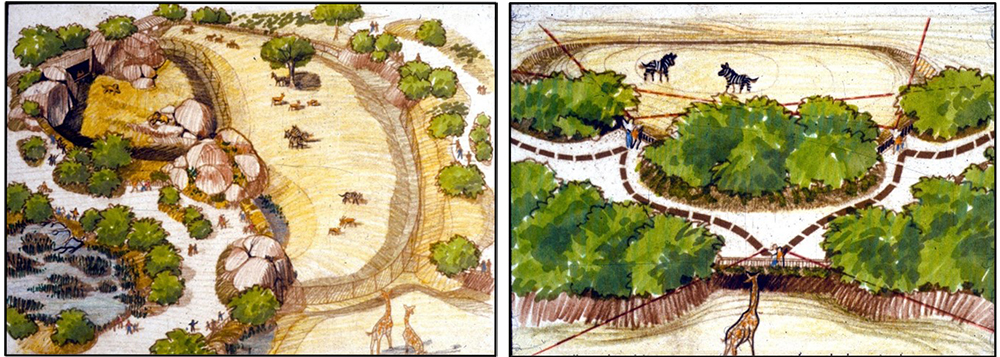

In the first photo visitors are outside a naturalistic wolf exhibit looking in. The second photo shows visitors immersed in a simulated tropical forest looking into a gorilla habitat in the same forest and separated by a hidden barrier.

Highly authentic and immersive gibbon exhibit in Tokiwa Zoo Yamaguchi, Japan designed by Dr Kenji Wako also has Sumatran cultural features.

What today I call “Deep immersion” exhibits such as those at Woodland Park and Bronx Zoos and areas of Disney’s Animal Kingdom (which also excels in high quality cartoon representation), create a highly detailed and many layered presentations of nature and culture. The goal is to convey an emotional sense of believability and authenticity to the casual, incurious visitor, while engaging even expert geologists and biologists with highly nuanced and detailed representations of natural forms suggestive of timeless natural processes. We were of course being true to our own natures, designing to our own deep satisfaction perhaps.

The “landscape immersion” term and approach were developed in 1975 by Grant Jones, Dennis Paulson, Jon Coe, and David Hancocks for Woodland Park Zoo. However, the idea of designing for people to pass through and be immersed within, rather than alongside the theme landscape, was developed earlier by Mr. Merv Larson at the Arizona Sonora Desert Museum, Dr George Rabb in the Predator Ecology Exhibit at Brookfield Zoo, and the Bronx Zoo African Plains Exhibit and independently later by Mr. Dwight Holland at North Carolina Zoo. However, the Jones & Jones team, Including Jon, were the first to publish the design principles and processes for creating immersion displays. Today, nearly fifty years later, the term “immersive display” is applied to any type of experience of whatever type that is deeply engaging.

Landscape immersion design sets up respectful emotional connections to animals and nature by immersing zoo visitors in dramatic unfamiliar landscapes, using sequential choreography and controlled sight lines to reveal the desired story and hide distractions.

Cultural Resonance

The landscape or habitat immersion concept was expanded by Grant Jones and others to include vernacular architectural and cultural environments in zoo exhibits. This concept was first developed by Carl Hagenbeck in 1907 and was revived and expanded in the 1980’s. It adds an important human dimension to immersion design tremendously increasing education opportunities and value.

Examples of cultural resonance. Left: Thai Elephant Temple at Woodland Park Zoo by Johnpaul Jones of Jones & Jones. Right: Ranthambore tiger exhibit at the Bali Safari and Marine Park by Jon.

This concept has made a strong comeback… in recent zoo exhibits at Zoo Atlanta, Bronx Zoo, Woodland Park Zoo, and several others. These current exhibits emphasize the interrelationship between traditional peoples and wildlife, point to a more naturalistic lifestyle alternative and, in some cases, alert visitors to the parallel extinction of wilderness and traditional cultures.

From “The Evolution of Zoo Animal Exhibits ” by Jon Coe, 1992 in The Role of Zoos and Biological Conservation: Past, Present and Future for a symposium 1992 AAZPA National Convention.

An essential feature of adapting cultural forms is always to present the culture respectfully, including involving local ethnic communities in the design process. The term “Cultural Resonance” was first used by Grant Jones and Woodland Park Zoo.

Cartoon Naturalism

There is a rapidly growing zoo exhibit style which attempts to immerse visitors in stage set recreations of natural and cultural landscapes. When compared to the highly realistic “Deep” landscape and cultural immersion exhibits previously described, these are more symbolic, just as cartoon representations are simpler and more symbolic than realism in illustration and storytelling. Like cartoon graphics, they seem to appeal to visitors seeking a quick and bite-sized understanding of the story being presented. Cartoon immersion, with easily recognized clichés exemplified by what may be called “zoo rock” or “mock rock” (in contrasted to museum-quality geology) designs to the level of light entertainment.

Here are two obvious examples of Cartoon Naturalism, one quite old and one quite new. The left photo shows a goat rock formation copied from the Hagenbeck style as a postage stamp sized mountain. This is a common old zoo cliché. As is too often the case, historic preservation laws prevent removal of this structurally unsound exhibit area no longer meeting today’s management standards and infringing upon the backdrops of new display areas. On the right is a contemporary example of “mock rock” shaped not by natural shoreline erosion, but to fit glazing standards. This is a common modern zoo cliché.

This platypus display represents an abstract egg since platypus are egg laying mammals. But the flamboyance of the cartoon architecture overwhelms and distracts from the animals it is intended to display in what is otherwise a highly naturalistic native animal park.

Authenticity

This designed, constructed, and maintained boreal landscape with bears and mountain goats in the Northern Trail exhibit at Woodland Park Zoo” feels’ completely authentic. Even an Alaskan park naturalist would agree because one helped to build it. Photo: L. Sammon.

Experts in fields ranging from the arts, entertainment and marketing recognize the importance of authenticity in selling their brands or products. The ‘real deal’ is unusually more valued than the copy, the counterfeit, and the cliché. But what are we to make of authenticity in the world of synthetic reality? What does authenticity have to do with zoo, aquarium, museum, and theme park exhibits? Sceptics would say, ‘it’s all fake anyway!” Authenticity lodges in the thoughtfulness, depth and skill embedded in the preparation and maintenance of the synthetic artefacts and simulated landscapes. Are they masterfully created and presented? Do they have real depth of meaning and does each layer richly reveal more to the story and the experience? Does the observant visitor gain more with each visit as a good novel, poem or sonata reveals more with each reading or listening? Noted Japanese zoo designer Dr Kenji Wako described the feelings he experienced after visiting the deep immersion gorilla exhibit at Woodland Park Zoo as being like the deep satisfaction he felt leaving an excellent concert.

In the end, the degree of “cartoon” or “authenticity” developed for the visitor experience is determined by the appreciation of the consumer, in this case the zoo and aquarium visitor, as well as the director and board of governance. Do they recognize and value levels of authenticity and are they willing to build and maintain them?

This designed, constructed, and maintained boreal landscape with bears and mountain goats in the Northern Trail exhibit at Woodland Park Zoo ‘feels’ completely authentic. Even an Alaskan park naturalist would agree because one helped to build it. Photo: L. Sammon.

Experts in fields ranging from the arts, entertainment and marketing recognize the importance of authenticity in selling their brands or products. The ‘real deal’ is unusually more valued than the copy, the counterfeit, and the cliché. But what are we to make of authenticity in the world of synthetic reality? What does authenticity have to do with zoo, aquarium, museum, and theme park exhibits? Sceptics would say, ‘it’s all fake anyway!” Authenticity lodges in the thoughtfulness, depth and skill embedded in the preparation and maintenance of the synthetic artefacts and simulated landscapes. Are they masterfully created and presented? Do they have real depth of meaning and does each layer richly reveal more to the story and the experience? Does the observant visitor gain more with each visit as a good novel, poem or sonata reveals more with each reading or listening? Noted Japanese zoo designer Dr Kenji Wako described the feelings he experienced after visiting the deep immersion gorilla exhibit at Woodland Park Zoo as being like the deep satisfaction he felt leaving an excellent concert.

In the end, the degree of “cartoon” or “authenticity” developed for the visitor experience is determined by the appreciation of the consumer, in this case the zoo and aquarium visitor, as well as the director and board of governance. Do they recognize and value levels of authenticity and are they willing to build and maintain them?

Activity-Based Design

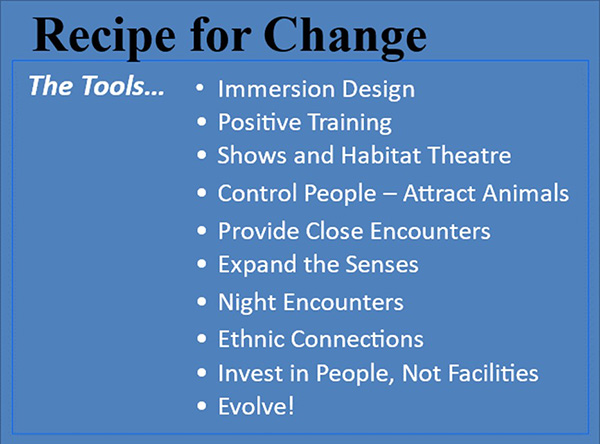

“Activity-based design emphasizes behavioral management as advocated by Hediger in the 1950’s. This concept was updated in the 1980’s to integrate the fields of behavioral enrichment, animal training, husbandry, and design. Improved animal activity and fitness levels result in more active and interesting animal displays.

Positive reward training (PRT) is an essential component of activity-based design and management. See the Animal Husbandry Section for importance of training for optimal animal care. Photo: Louisville Zoo.

“Activity-based design begins with the premise that the animals’ long-term well-being is paramount and that environments, programs and procedures which advance this goal are frequently of great interest to the visiting public. Healthy animals with stimulating behavioral choices tend to be more active. Therefore, opportunity-rich animal environments, enlightened animal care and caretaker devotion should all be made visible to the public within a setting which demonstrates the animals’ innate competence.”

Quote from “Entertaining Zoo Visitors and Zoo Animals: An Integrated Approach” in 1997 AZA Convention Proceedings by Jon.

Affiliative Design

Photo: Dallas Zoo.

All social species have both affiliative and agonistic behaviors and environmental as well as social settings can encourage one or the other. Thus, creating environments and social settings encouraging friendly, affiliative behavior from both animals and viewers reduces management problems and increases visitor enjoyment.

Building a bond between people and the planet”, the Louisville Zoo motto, describes one of the major roles of zoos. Building upon the work of Hediger, Lorenz, and contemporary behaviorists, affiliative design provides positive opportunities to enhance the natural sociability of people and other primates, encouraging them to enjoy each other’s company. What could be more natural? What could be more important for building the early and lasting bonds needed to support the long-term survival of endangered primates and other species in our human-dominated world?

Quote from “Increasing Affiliative Behavior Between Zoo Animals and Zoo Visitors” Jon Coe for 1999 AZA Convention Proceedings. This concept was developed by Jon Coe at CLRdesign, inc.

Animal Rotation (Alternation or Flex Exhibits)

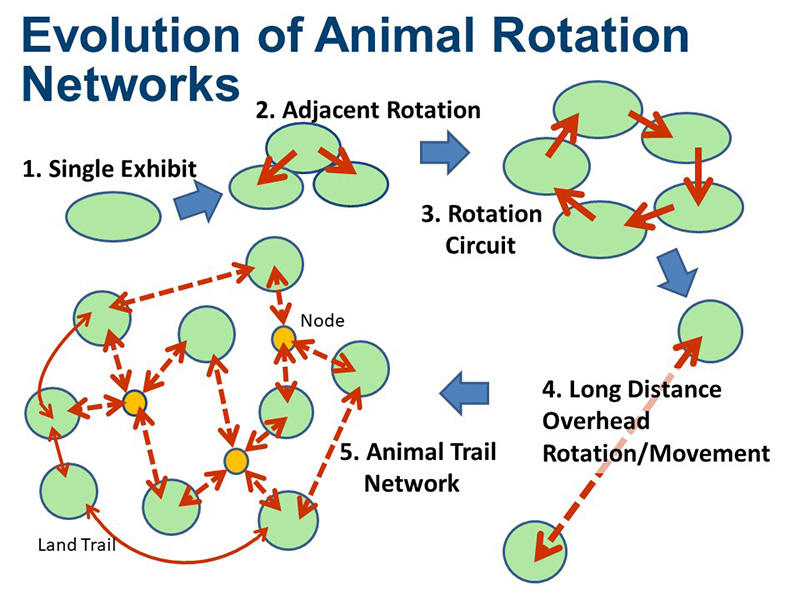

Why should zoo or sanctuary animals be limited to living in the same area, even a very nice area, for their entire life? Why can’t they “time share” with adjacent neighbors having similar requirements? Zoos have long displayed mixed species of compatible animals sharing common areas concurrently (at the same time). All animals must be free of contagious diseases and barriers must be robust enough for the strongest or most agile species and individuals. Why not have mixed species exhibits where the animals share the same areas consecutively (at different times)?

Immersion exhibits have changed animal zoo exhibition using ‘nature’ as the model, yet even the most diverse zoo habitats don’t provide animals interesting and challenging behavioral opportunities to fully develop natural species capabilities. Animals soon become habituated with resulting decrease in animal activity and visual interest for the public. Having various individual animals or groups transfer between different exhibit areas on a regular basis during the day or week can combine all the concepts of immersion design, themes, storylines, and culture elements with activity-based training to add to the impact of zoo exhibits for both visitors and animals.

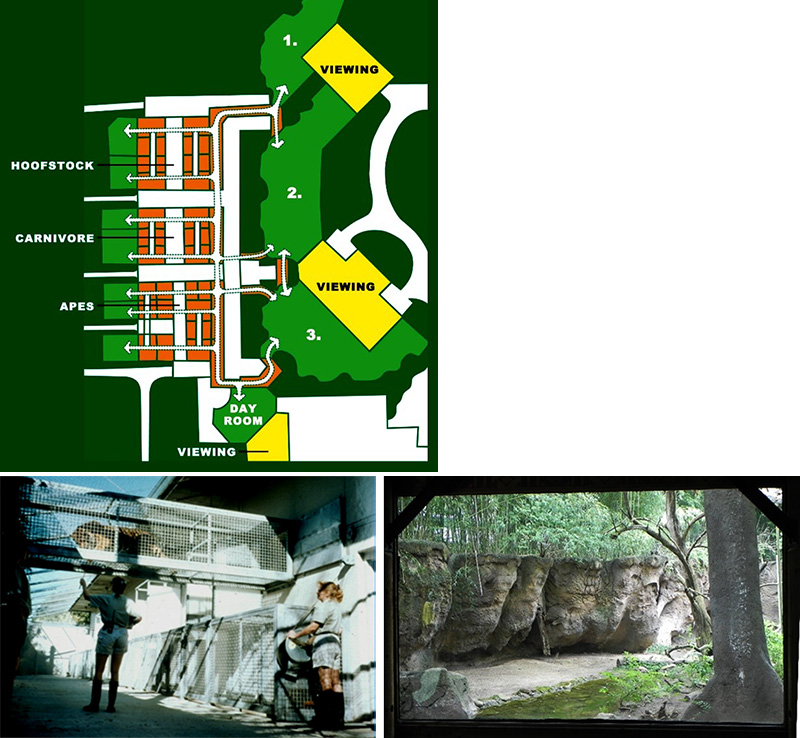

Upper image shows the Islands plan with night quarters on the left connected to four display areas (photo on lower right) by a lengthy system of off-exhibit raceways (lower left photo). “Mixed Species Rotation Exhibits” [link?] by Jon Coe for 2004 ARAZPA Annual Conference. This concept was developed by Jon Coe and Gary Lee at CLRdesign, inc.

At Louisville’s (Kentucky USA) Islands Exhibits orangutan, tapir, babirusa, siamang and Sumatran tiger rotate through four habitat areas on a randomly determined schedule. Two years of behavioral observations show normal stress levels, increased activity, and previously unseen natural behaviors. [White, B., et al. 2003. Activity-based exhibition of five mammalian species: evaluation of behavioral changes. Zoo Biology 22(3): 269-285.]

I don’t think I could go back to a traditional type of exhibitry for anything new we created. It’s just so boring to me!

Jane Anne Franklin, Mammal Curator/ Supervisor of Animal Training, Louisville Zoo

Trailways

I really like this concept as an animal behaviorist it totally makes sense, and I am sure it must be very good for the psychological wellbeing of the animals. Not to mention that the zoo is no longer a static place – it is dynamic like the wild and the public will need to seek out the animals. Great to see that you keep pushing the boundaries on enclosure design and modification.

Dr Robert John Young, University of Salford, Ecosystems and Environment Research Centre.

Both traditional zoo exhibits, and rotation exhibits sometimes connect display areas and night holding areas with short raceways, linear enclosed links. But if these links were greatly elongated, could they become more than functional connections? Could they also become animal activity areas and displays? Could they become animal trails, both terrestrial and arboreal, connecting important resources in ways similar to trails used by wildlife? And could they be used alternately by many species on a time-sharing rotational management program?

The Center for Great Apes in Wauchula, FL lead the way twenty years ago and now has a network of 2.4km of overhead trails for rescued chimpanzees and orangutans.

Big Idea: Why can’t we hook up everything in the zoo to everything else and basically let the animals have the run of the place? (Jon Coe 2009)

Philadelphia Zoo, with their Zoo360 program: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Zq4HjpoHxkk Jon helped to develop a plan to link their entire campus with trail networks through staged development of surface and overhead trails for smaller primates (500m), great apes (200m), big cats (200m), and domestic animals with children. Future stages include bears and hoofed animals.

International examples of animal trails. Upper left, Zoo Guadalajara, Mexico. Upper right and middle left, (photos: Adelaide Zoo), Australia. Lower right photo from Safari World, Bangkok, Thailand by D Nagel.

O-Lines

Photos: Left at the National Zoological Park in Washington DC and right at the Auckland Zoo, New Zealand

Dr. Ben Beck of the Smithsonian National Zoo in Washington DC was first to develop an overhead trail way of cables for orangutans to brachiate from their older Great Ape House to the new Think Tank cognitive research and display facility. This opened 1995 and is 122m long (left photo). Since then, many other O-lines have been developed in Japan, Mexico, Singapore and, most recently in New Zealand. These facilities are typically linear down-and-back routes, but the new Auckland Zoo exhibit (right photo) O-line is organized in a triangular network, providing the apes more travel choices.

Functional Modernism

The modernist movement in architecture appeared in London Zoo with their abstract functional penguin exhibit in 1934. The modernist idea of “functional naturalism” uses synthetic materials and structures to create environments and features allowing natural animal behaviours, has become a common and at times dominant approach to zoo design. This approach is based upon practicality, and perhaps also an anthropocentric design philosophy that human creativity and technology can meet all our needs synthetically. This remains the dominant approach for design of non-public animal management areas such as night building and animal health facilities. The previously mentioned “Trailway” and “O-Line” design trends also depend upon this approach but can be “softened” by locating them within park or natural habitat landscapes. Another successful use of this approach is in the design of indoor day rooms, group, or herd rooms, where animals are displayed during inclement weather and in the best cases have 24/7 access when they desire it.

Functionally modern facilities can use “soft architecture” as defined by Robert Sommer or “hard architecture” of rigidly fixed steel and concrete and increasingly, touch screen computers and automated feeding devices.

“Soft” architectural indoor display and exercise areas with 24/7 access by great apes. Denver Zoo on left and Louisville Zoo on right. These examples were designed by Jon with CLRdesign.

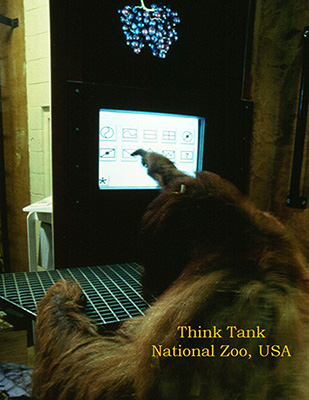

Animal Computer Interactions (ACI)

A promising frontier in management, research and environment enrichment for wild, zoo, pet, and food production animals is the incorporation of automation, remote control, data gathering, and especially animal control of enrichment opportunities. While well advanced in industrial agriculture, future ACI development may be redirected to providing animals in managed care greatly increased agency, “choice & control” in managing their own lives.

Dr Julia Hoy, Research Manager, Hidden Vale Wildlife Centre, University of Queensland, and colleagues invented the “Smart Gate” and “Smart Feeder” now commercially available from UK based company Sureflap ® These photos and findings are provided by Dr Hoy. “Microchip-automated technology can provide captive wildlife with an extensive and variable variety of food, enrichment, and access to space on an individual animal basis, to more accurately replicate aspects of the natural environment: potentially improved welfare of captive wildlife.” Julia Hoy

Microchip activated access to a remote artificial burrow. “Microchip-automation can be used as a tool in wildlife soft-release programs by facilitating individual animal access to resources (e.g., food, refuge from predators) while also allowing ongoing monitoring of released animals: potentially improved conservation outcomes.” Julia Hoy

Orangutan controlled light show and game. In 2015 the University of Melbourne Social NUI Centre (funded by Microsoft Research and the Victorian State Government) collaborating with Zoos Victoria, developed an animal interactive system using a Microsoft Kinect device as a temporary research project and proof of concept. (Photo: Zoos Victoria). For more information see: Webber, S.; Carter, M.; Sherwen, S.; Smith, W.; Joukhadar, Z.; Vetere, F. Kinecting with orangutans: zoo visitors’ empathetic responses to animals’ use of interactive technology. In Proceedings of 2017 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 2017; pp. 6075-6088.

Touch screen computers have long been used in cognitive research as this photo from 1995 demonstrates. Recent research shows that many primates enjoy these programs as well and, when available, use them during times researchers are no longer present. There is ongoing research in adapting virtual reality technology for use by bonobos living in laboratory facilities without access to large outdoor enclosures.

The Unzoo Alternative

Zoos as we know them are based upon the twin limitations of animal containment and coercion. But positive reinforcement training has made animals collaborators in their own care, removing the need for coercion except during emergencies. What if we contained the people rather than the animals? Safari parks do this. Perhaps this also can be done at a pedestrian scale? What if we responsibly used rewards to encourage free-ranging wildlife to collaborate in our education and conservation programs? This is an aspirational concept, although embraced and in a transition stage between zoo and unzoo in two Australian native fauna parks, the Tasmanian Devil Conservation Park in Tasmania, and the Kyabram Fauna Park in Victoria, Australia.

Left photo, children contained, Tasmanian devil in large enclosure. Right image, people contained, surrounded by tigers.

Read more about Zoo Exhibit Trends

Jones, G. R., Coe, J. C., and Paulson, D. R. 1976. Woodland Park Zoo: Long-Range Plan, Development Guidelines and Exhibit Scenarios, Jones & Jones for Seattle Department of Parks and Recreation. Reissued: Coe, J.C. 2004. Woodland Park Zoo Long-Range Physical Development Plan. CLRdesign. Available from Woodland Park Zoo. See also 2004 update to plans.

Coe, Jon C., 1982. “The Coe-Jones Rules for Immersion Exhibit Design” self-published

Coe, Jon C., 1985. “Design and Perception: Making the Zoo Experience Real” in Zoo Biology, vol. 4 no. 2, pp. 197-208.

Coe, Jon C., 1989. “Children’s Drawings May Make Good Evaluation Tools for Zoo Exhibits” in Visitor Studies 1988: Theory, Research and Practice, S. Bitgood, J. Roper, A. Benefield, Eds. Center for Social Design, P. O. Box 1111, Jacksonville, Alabama 36265. Abstract

Coe, J. C., 1989. The Genesis of Habitat Immersion in Gorilla Exhibits, Woodland Park Zoological Garden & Zoo Atlanta, 1978- 88. (Published 2006) Abstract.

Coe, Jon C., 1994. “Landscape Immersion – Origins and Concepts” in “Landscape Immersion Exhibits: How Are They Proving as Educational Settings?” J. Coe, Moderator, 1994 AZA Convention Proceedings, American Zoo and Aquarium Association, Bethesda, MD. Abstract.

Coe, Jon C., 1995. “Zoo Animal Rotation: New Opportunities from Home Range to Habitat Theater” in AZA Annual Proceedings 1995, Wheeling, WV, pp. 77-80. Abstract.

Coe, Jon C., 2003. “Landscape Immersion Exhibits & Beyond” in Proceedings of SAGA Symposium, Tokyo (Lecture).

Coe, Jon C., 2004. “Mixed Species Rotation Exhibits”, 2004 ARAZPA Conference Proceedings, Australia, on CD. Abstract.

Coe, Jon C. and Mendez, Ray, 2005. “The Unzoo Alternative” , 2005 ARAZPA Conference Proceedings, Australia, on CD. Abstract

Coe, Jon, 2014. “Next Generation Rotation Exhibits – Raceway Networks and Space to Explore ” Zoo and Aquarium Association Annual Conference, 25-28 March 2014, Auckland NZ.